A fuller version of this research was published on the Journal of Economic Analysis. Read it here

Introduction

The startup ecosystem in Southeast Asia has witnessed significant growth in recent years, attracting a growing number of entrepreneurs, investors, and accelerators. Startup funding is a critical aspect of entrepreneurship, and the ability to secure venture capital investment is often a key determinant of a startup’s success. While numerous factors contribute to the likelihood of securing funding, the educational background of the startup’s founders is often, but only anecdotally, considered to be a significant factor. This report aims to explore the relationship between the educational background of startup founders in Southeast Asia and their ability to secure venture capital investment.

There exists a limited amount of research on this topic. In Tamaseb (2021), we learn that the founders of billion-dollar companies were more likely to have PhDs than be dropouts and that in 45% of these unicorns, co-founders either went to the same school or worked at the same company at some point. However, the study is silent on the impact of the pedigree of the educational institutions.

Glasner (2019) looks at which US institutions churn out the most graduating startup founders who have raised at least US$1m, in which UC Berkeley, UCLA, and the University of Michigan come out on top.

More recently, Kushida (2023) examines, among other things, the educational background of the 15 most-funded startups in Japan, noting that the universities of Tokyo, Keio, and Waseda, which were by far the three most prominent names, are also Japan’s top-ranked universities and produced the largest number of founders.

However, to the best of our knowledge, there has been limited research on the relationship between the educational background of startup founders in Southeast Asia and their ability to attract venture capital investment. To this end, this report will examine data on startup founders in Southeast Asia and their educational backgrounds, using a dataset compiled from publicly available sources such as Pitchbook and LinkedIn. Specifically, the report will compare the funding received by startup founders who graduated from one of the top 30 universities in the world to those who did not. The report will also explore the factors that contribute to the likelihood of securing funding in Southeast Asia and whether the educational background of founders is a significant factor.

Overall, this report aims to contribute to a deeper understanding of the relationship between educational background and startup funding in Southeast Asia. By shedding light on the factors that contribute to the likelihood of securing funding in this region, this report will provide valuable insights for entrepreneurs, investors, and policymakers alike.

Methodology

The purpose of this report is to investigate whether startup founders in Southeast Asia who graduated from one of the top 30 universities in the world receive more investment from venture capital than startup founders who did not attend one of these universities. Anecdotally, the intuitive answer from different players in the startup scene is that an elite education background certainly helps to get more investment, as the prestige of the institution attended at the very least signals certain credentials such as specific skills or access to powerful networks. However, no quantitative analysis has been done on this question.

To accomplish this, we first extracted a list of 900 startups with headquarters in Southeast Asia from Pitchbook, specifically shortlisting those that raised funding after 2017. Pitchbook is a financial data and software company that provides information on global private equity, venture capital, and mergers and acquisitions. The data extracted from Pitchbook included information on the latest funding size and the latest financing deal type for each startup on the list, which was categorized into “seed round”, “early stage” (series A and B), and “late stage” (series C and D). Although this list of companies was comprehensive, it was certainly not complete, as we knew of a few startups that were missing from the list. We attribute these absences to random clerical errors on the Pitchbook side, and do not identify any specific bias in this list.

Next, we manually looked at each of the 900 startups and took note of the educational details of the founders. We found this information mainly on LinkedIn, but sometimes through search engines. We recorded where each founder went for undergraduate and post-graduate studies. However, it was important to note that it had to be a full-time program for it to count. Online or short-term courses, even those from prestigious institutions, were excluded. Additionally, executive MBAs were also not counted, since the exact nature of some of those programs is less clear and might actually fall under the category of a short-term course.

In choosing which founders within each startup to focus on, we always prioritized the CEO first. For a second co-founder (CXO), where relevant, we established a hierarchy as follows: co-founders came first, followed by those with a Chief Operating Officer (COO) title and then finally those with any other title. If there was no co-founder, but there was a Chief Technology Officer (CTO) who had started well before the latest funding round, we took those details instead. In cases where a company only had one founder and no one else with the CEO role could be found, we assumed that this person was the CEO regardless of their actual title.

For these reasons, the data on co-founders was always going to be a bit more noisy. The objective of collecting this secondary data was to try and understand whether any possible impact from attending an elite institution needed to come from the CEO or could be any (or all) of the co-founders.

One of the biggest challenges we faced during this study was connected to people’s privacy settings. While most people could be found on LinkedIn, some founders had a very faint digital footprint. This was especially the case with founders of web3 and crypto startups, where anonymity and privacy are strong values in the community.

After creating this list of startups and founders and noting their educational backgrounds, we assigned a ranking to the universities based on whether they were in the top 30 worldwide. To determine which universities qualified as a top 30 school, we used a ranking created by USNews for the academic year 2022/2023. We understand that this is a contentious issue and that many top schools may be left out of this ranking. However, we used this ranking to ensure consistency in our analysis. There were three Asian universities on this list: Tsinghua, the National University of Singapore, and Nanyang Technological University.

In the event we could not find the founder’s university background, we assumed that it was not a top 30 institution.

We then used an Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression to assess whether having attended elite institutions at the undergraduate or graduate level was correlated to the amount of funding raised at different stages of a startup.

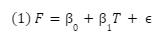

We initially expressed the process as follows:

Where F refers to the latest funding size and T is a dummy variable that captures whether or not the CEO went to a top school.

We then added in dummy variables to accommodate the three different funding stages:

Where E is a Dummy variable that takes value 1 when the latest funding being raised was at the Early stage (series A and B) and 0 otherwise and L is a dummy variable that takes value 1 when the latest funding being raised was at the Later stage (series C and D) and 0 otherwise. ST, ET and LT are multiplicative dummies where T was defined above and S is a dummy variable that takes value 1 when the latest funding being raised was at the Seed stage and 0 otherwise. The statistical significance of the multiplicative dummies will tell us whether attending a top school affects the amount raised in any of the stages. The comparison will be in relation to the amount raised by a CEO who has not attended a top school at the seed stage.

We used this model to examine CEOs who have attended elite schools at the undergraduate level and then at the graduate level, that is we run different regressions with different definitions of the dummy T.

Finally, we also run the regressions looking at the founding team as a whole. In other words we define our dummy variable T as taking value 1 when at least one of the two founders went to a top school and 0 when neither of them did.

Results:

Descriptive analysis

| Last Financing Deal Type | Total number of CEOs | # CEOs with regular undergrad | # CEOs with top undergrad | # CEOs with no postgraduate degree | # CEOs with regular postgraduate degree | # CEOs with top postgraduate degree | |

| Seed Round | 320 | 270 | 50 | 191 | 81 | 48 | |

| Early Stage VC | 378 | 300 | 78 | 219 | 86 | 73 | |

| Later Stage VC | 59 | 48 | 11 | 31 | 13 | 15 | |

| Grand Total | 757 | 618 | 139 | 441 | 180 | 136 |

From the original sample of 961 entries extracted from Pitchbook, we removed those which were at different stages of funding from the three categories we were looking for (Seed Round, Early Stage VC, Later Stage VC) or whose stage was not given. From the remainder, we also removed those startups for whom we could not find a founder or CEO. Once we had removed all these, we were left with a sample of 757 startups.

Looking at the CEO’s undergraduate background, 139 of them, or 18% of the sample, went to a top 30 university (Table 1). This proportion was consistent among the three financing deal types.

Looking beyond the undergraduate level, 316 CEOs, or 42% of our sample, had attended some sort of graduate program (Table 1). Among those, 136, or 43% of all grad school attendees, were from a top 30 university. Of those who went to graduate school, 43% of them had an MBA (Table 2). Half of the MBA holders received it from a top university.

| Last Financing Deal Type | No MBA | MBA | Of which from top school |

| Seed Round | 270 | 50 | 20 |

| Early Stage VC | 304 | 74 | 39 |

| Later Stage VC | 47 | 12 | 8 |

| Grand Total | 621 | 136 | 67 |

Looking at co-founders (Table 3), 230 startups, or 30% of our sample, did not have a co-founder. Of the remainder that did have a co-founder, 15% went to a top undergraduate school.

| Last Financing Deal Type | No CXO | # CXOs with regular undergrad | #CXOs with top undergrad | #CXOs with regular postgraduate degree | #CXOs with top postgraduate degree | |

| Seed Round | 98 | 196 | 26 | 52 | 28 | |

| Early Stage VC | 108 | 223 | 47 | 69 | 47 | |

| Later Stage VC | 24 | 25 | 10 | 8 | 8 | |

| Grand Total | 230 | 444 | 83 | 129 | 83 |

Similar to CEOs, 40% of co-founders attended graduate school (Table 3). However, co-founders were more likely to have attended a top school (39%) than CEOs. There may be some bias here as previously mentioned in the methodology, although it is likely we are capturing the advanced skillset of technical co-founders, especially from those startups more focused on the sciences.

Deal size distribution analysis

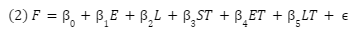

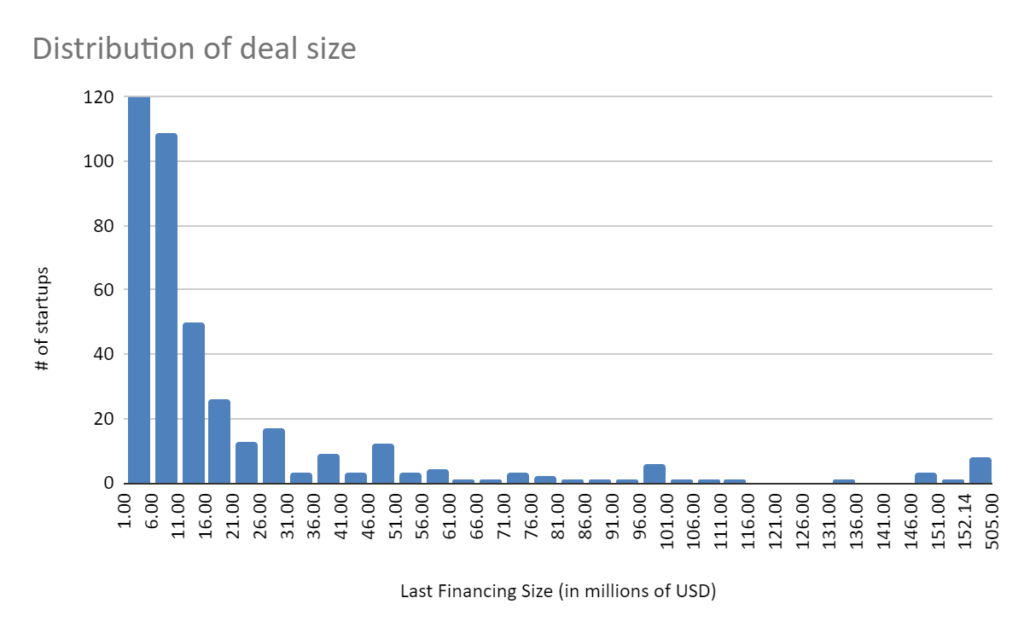

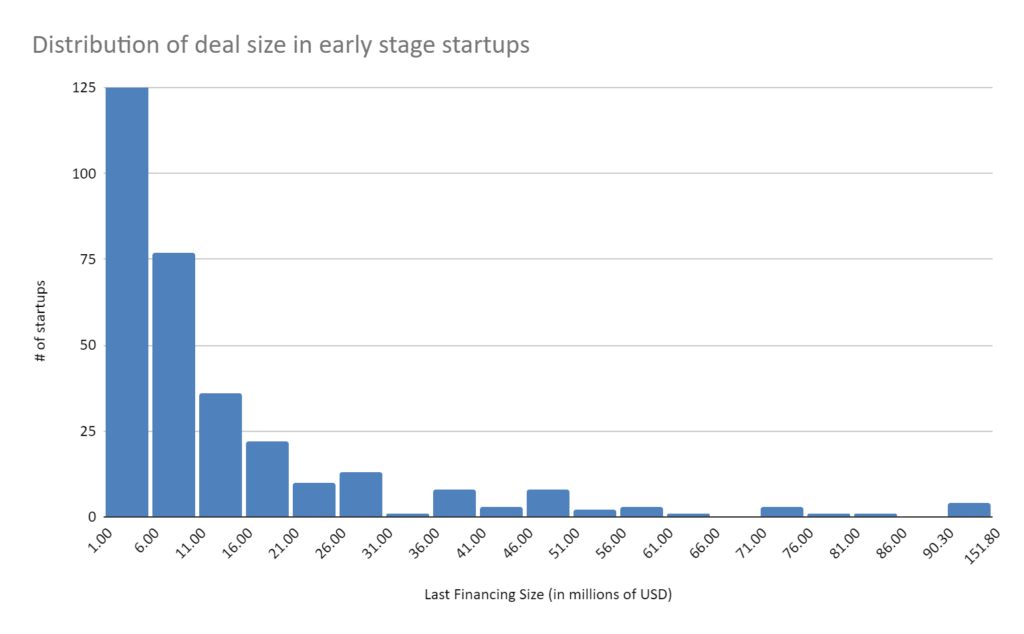

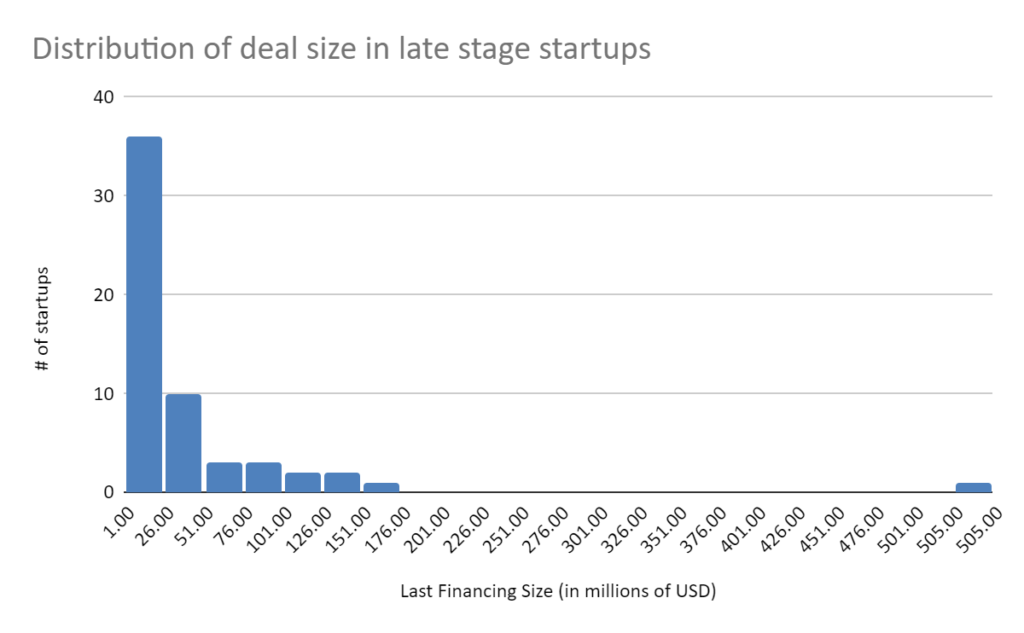

We examined the distribution of the deal sizes. As expected, this distribution has a very long tail due to the fact that a) there are fewer startups in later stages relative to earlier stages, and b) very large deals are quite rare (hence terms like unicorn). This distribution follows a similar pattern overall and across each of the three financing deal types considered here. (note that some outliers have been removed from the seed stage and early stage charts for clarity, though they have not been removed from subsequent analysis)

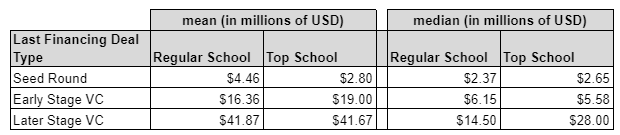

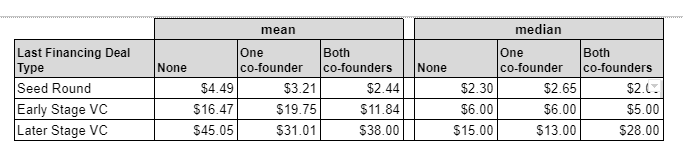

We next looked at both the mean and the median funding size at each stage, taking into account whether or not the CEO attended a top undergraduate school (Table 4).

As expected, the median values tend to be much lower than the mean values, as the very large deals from the long tail of the distribution pull the mean upwards significantly. Nevertheless, we seem to see a similar story in both cases, in which there does not appear to be much of a difference in the amount raised by founders who attended a top undergraduate university worldwide and founders who did not. Two potential exceptions that stand out are the difference in mean values at the seed round, where in fact CEOs who went to an elite university seem to raise less, and the median values at the Later Stage, which suggest that elite-school CEOs are raising almost twice as much. We confirm whether these differences are statistically significant later during our regression analysis.

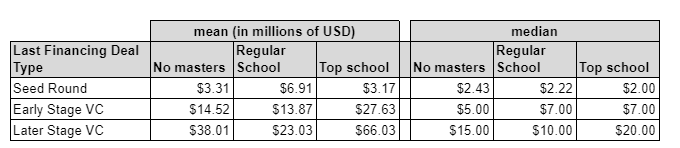

Next, we performed a similar analysis, this time considering the CEO’s postgraduate education, if any (Table 5). Starting with the means, we seem to see an increasingly larger difference in funding size between CEOs who went to a top post-graduate school and those who didn’t, or did not attend at all, as the financing deal type matures. The median tells a similar story as with the undergraduates, where there is a seemingly large difference in the medians at the later stages of startup financing.

Finally, we looked at the difference in means and medians, taking into account the educational pedigree of the second co-founder (Table 6). In the table above we considered the case when neither co-founder went to a top school, when at least one co-founder did, and when both of them did.

Regression analysis

In this section we follow a similar order of analysis as in the previous section, this time running different regressions with added variables. We expand the analysis further by asking deeper questions about the influence that the educational background of co-founders might have.

CEO’s Undergraduate Education

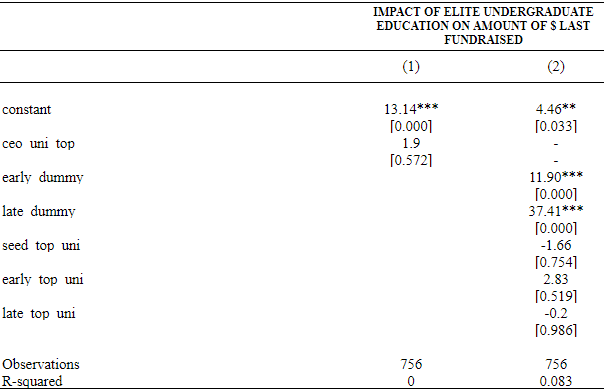

We begin by examining the correlation between having attended an elite undergraduate school and the size of the most recent fundraising round only.

We noted the lack of significant correlation in our first equation. We continued the analysis by adding the three funding stages as dummy variables, as seen in the second column (equation 2). Again we find no statistically significant effect of an elite undergraduate education on the last fundraising round.

CEO’s postgraduate education

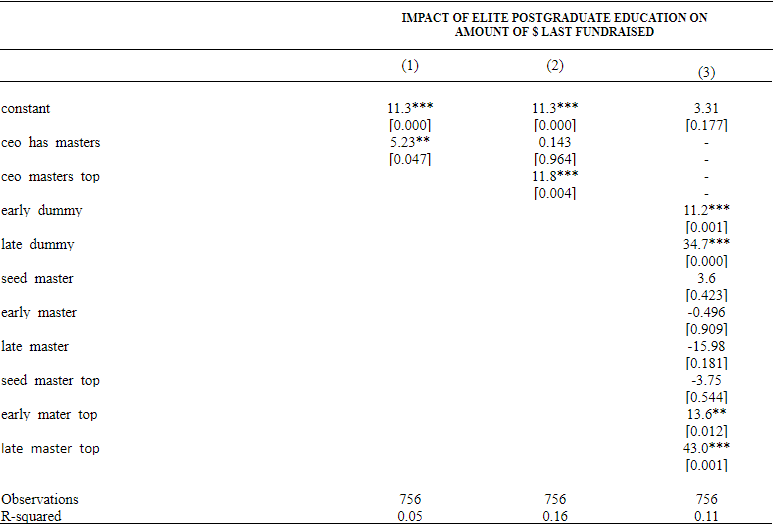

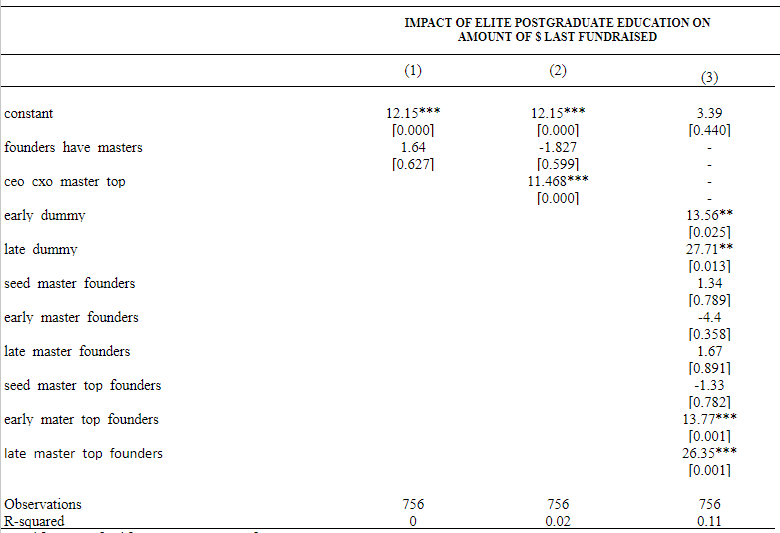

Next, we repeated the analysis by looking at the CEO’s postgraduate education. First, we examined whether having any kind of masters is correlated with greater financing as shown in column (1) below.

We see that there is a positive and significant effect. Next, we added a variable to the regression to see the effect of having attended an elite postgraduate school, in column (2). We see from this regression that the effect from the previous regression was coming from the subsection of founders who went to top postgraduate school, as the dummy variable for having attended an elite school has a positive and significant effect, whereas the dummy variable of having any postgraduate becomes insignificant and near zero.

Next, we tried to understand if this effect is significant across the different rounds of financing, so we included the variables for the various deal types – column (3). From this regression we see that at the seed stage there does not seem to be any effect from having a postgraduate degree, regardless of the pedigree of the school. In later stages, however, we see a significant and positive effect between having an elite master’s degree and raising money, an effect that intensifies at later stages.

Co-founders’ undergraduate education

Finally, we look at whether there is any additional effect when we look at the educational pedigree of the founding team and not just the CEO, that is, when we also consider the educational background of the co-founder.

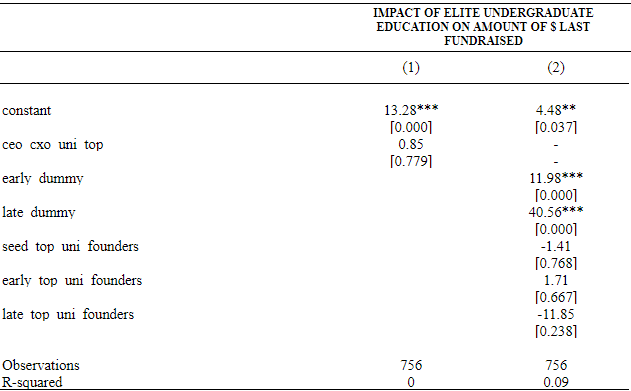

We begin at the undergraduate level, first looking at any effect from at least one of the founders having gone to an elite undergraduate school.

Similar to the scenario where we exclusively examined the CEO’s educational background, there appears to be no significant effect in fundraising from having at least one of the founders with an undergraduate degree from a top university.

As before, we proceed to investigate whether the effect varies at different stages of funding, and once again, we observe no significant impact on funding at any deal size.

Co-founders’ postgraduate education

Lastly, we examine postgraduate education, whether having at least one of the co-founders from an elite institution has any effect on fundraising. As before, we first explore if either co-founder holding a postgraduate degree has an impact on financing (1):

Unlike the previous instance, where having a postgraduate degree had a positive and significant effect, when we include the educational background of the CTO/co-founder, that effect becomes insignificant.

We continue by distinguishing those postgraduate degrees that come from elite schools (2). We can clearly see the positive and significant effect from elite postgraduate education on the amount raised from VC, a result consistent with what we found when only looking at CEOs.

Lastly, we include variables for the different funding stages to determine if this effect is consistent across the board or only at specific stages (3). Indeed, and as before, the significant and positive effect is observed only in the later stages (Series A and onwards), whereas we cannot discern a significant difference in fundraising at the seed stage.

Discussion

The results of our study indicate a significant and positive relationship between having attended an elite university and the amount of funds a startup in Southeast Asia can raise. However, this effect becomes apparent only at later stages of fundraising and when the founders attended those top schools for their postgraduate studies, rather than for undergraduate.

These results may appear counterintuitive at first glance, especially considering that founders typically raise funds at the seed stage based on little more than a pitch deck. One might expect investors to look for other signals to help them estimate the chances of success. In fact, some VCs specifically and openly target founders with an elite school background. For instance, Loyal VC has a strong preference for founders who are either INSEAD or Founder Institute alumni. Nevertheless, our findings indicate that the correlation between the pedigree of founders’ education and the amount raised is limited during the early stage of investment.

This limited correlation may be attributed to the fact that seed-stage venture capitalists (VCs) do not base their valuations solely on the quality of the founders. Instead, they also consider the cash flow requirements of the startup. At such an early stage of the business lifecycle, as startups work to establish product-market fit, the amount of capital needed is limited, given that they have not yet entered the growth phase. In contrast, later-stage investment rounds emphasize growth, and the required capital levels may vary significantly depending on the startup type, the market it targets, and the nature of the business.

It is also possible that our dataset is not large enough to tease out any actual difference at a significant level, but it is also possible that what we are seeing instead is a binary effect where a disproportionate number of founders who come from elite schools are receiving any VC funding at all. Seed funding was fairly consistent in size across our data – the interquartile range is only $2.3m. Considering how many universities there are worldwide, it is unlikely that, everything else being equal, we would expect to get 18% of founders to come from the top 30 schools alone. Perhaps we are observing the chances of securing funding given an elite education background. However, this is difficult to demonstrate as we do not have the counterfactual of how many startups failed to fundraise from VCs.

This amplification of the elite school effect at later stages of funding could be attributed to various factors. For instance, it is possible that founders with elite postgraduate education are perceived as having superior skills, networks, or expertise, leading investors to place higher valuations on their startups. As companies progress through funding rounds, the importance of a strong leadership team with the ability to scale and navigate complex market dynamics becomes increasingly crucial. Consequently, investors may view founders with elite postgraduate education as better equipped to steer the company towards success in the long term, thereby justifying higher valuations and larger investments.

Furthermore, the elite school effect may also be indicative of the types of industries and ventures that founders with elite postgraduate education tend to pursue. It is plausible that these founders gravitate towards high-growth sectors or cutting-edge industries, such as deep tech, medtech, or other highly technical business models, which typically require larger amounts of funding and specialized expertise. As a result, the elite school effect may be partially influenced by the alignment between the educational background of the founders and the nature of their startups.

Moreover, founders with prestigious postgraduate education may have access to a more extensive network of alumni, mentors, and industry professionals, which could facilitate introductions to potential investors and strategic partners. These connections can be invaluable in securing larger funding rounds and establishing credibility within the startup ecosystem.

From the Tamaseb (2021) dataset, we know that the median age of founders, at the time of founding, is 34. In other words, more than half of the founders have been out of school for at least 10 years. Whatever may have been learned at university, top or otherwise, may not be necessarily relevant in a startup context.

In conclusion, as postgraduate education from prestigious universities appears to be important in later stages of fundraising, startups that lack key leadership with this background should consider adding a new member to the leadership team who possesses a strong postgraduate pedigree. By doing so, the startup would be better positioned to increase its ability to fundraise at later stages, potentially improving its prospects for growth and success in the long run. This new member could bring the necessary skills, expertise, and network connections that could significantly benefit the startup and its fundraising efforts, making it a strategic decision that could greatly impact the company’s future trajectory.

Areas of Further Study

This study should be considered as only the first step in better understanding the VC investing landscape in Southeast Asia. We are likely examining just one of many different factors that affect the decision to invest in a startup.

A first step would be a robustness test using a ranking from a different source or the ranking of a different year. While we do not expect the list of the top 30 schools worldwide to change dramatically from year to year, the inclusion or exclusion of certain universities might significantly alter our results.

Outside of robustness, within this particular study there were a few assumptions we made in our data that should be re-examined. First, we assumed that different countries in the region are likely to raise the same amount, all other things being equal, though this might not necessarily be the case – Singapore, for example, has a larger concentration of startups raising from VC but they may also have higher costs of production, so they may be raising more. Relatedly, we assumed that elite school graduates were evenly distributed across the startups in the region, but perhaps Singapore has a stronger gravitational pull because of higher salaries and the relatively higher level of educational institutions.

Second, we did not seek to distinguish between the different industries in the startup world. It may be possible that elite school graduates gravitate towards specific industries, or that specific industries inherently need to raise more in order to be able to build their product to completion. If the former is true we might be looking at an endogenous variable.

A specific mention should be made about startups in the web3 space. We observed that Web3 companies exhibited peculiar characteristics when compared to more traditional startups in Southeast Asia. A key contributing factor to this discrepancy was the preference of many Web3 founders to remain anonymous, leading them to adopt non-traditional funding methods such as tokens or Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs). This approach made it challenging to accurately determine the amount of funds these companies were raising, as the decentralised nature and anonymous participants in Web3 projects often obscured the funding process. This unique aspect of the Web3 space also serves as a reminder that the rapidly evolving nature of technology and the startup ecosystem can present new challenges and considerations when analysing fundraising trends and dynamics.

Third, we did not consider the effects of fundraising on a particular year versus another. The different macroeconomic factors, from the pandemic to the war in the Ukraine to the looming tech and financial crisis, have affected different parts of the startup industry differently. The winners during the pandemic, such as e-commerce, have had to make drastic adjustments in a post-pandemic environment where fundraising in that sector has dried up.

These are just three potential factors that could help explain the amount of funds raised for any given startup at any given time. This is data that we either currently have in our dataset (year of fundraise, region) or that we could build (industry). However, combined with the other variables we used in our model, our dataset is unlikely to be large enough to be usable with a more sophisticated model.

[1] Tamaseb, A. (2021). Super founders: What data reveals about billion-dollar startups. PublicAffairs.

[2]Glasner, J. (2019, May 25). Which public US universities graduate the most funded founders? TechCrunch. https://techcrunch.com/2019/05/25/which-public-us-universities-graduate-the-most-funded-founders/

[3] Kushida, K. (2023, February 1). The People Powering Japan’s Startup Ecosystem. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/2023/02/01/people-powering-japan-s-startup-ecosystem-pub-88924

[4] https://pitchbook.com/

[5] https://www.usnews.com/education/best-global-universities/rankings